Life Stories Australia’s HEATHER MILLAR works as a volunteer with palliative care patients to record their memoirs. In this article, first published in Health Agenda magazine, she explores the benefits of telling your life story.

It was shortly before he died that my father asked my sisters and I to fly to Tasmania to witness his memoirs. We sat around the kitchen table for three days at his home in Hobart, looking out across the Derwent River, listening to him talk about his life growing up on the mountainous West Coast of New Zealand. We went on to have those stories transcribed, and I edited them and made up a booklet for family members.

Difficult though it was at the time, the process ignited something in me. I went on to volunteer at the Mary Potter Hospice at the Calvary North Hospital in South Australia as a biographer recording the stories of people who are in palliative care.

I have witnessed firsthand the value people get from reviewing their life in this way. I have seen them light up as they relate the stories of their lives. I have seen them not wanting to stop telling their stories when time is up for the day … as if they are clinging for dear life to the thread of their humanity, and if they cling hard enough, it will stave off the inevitable.

It also seems to be a process of making sense of one’s life – was it a good one? Did I do it well? Did I live it fully? Was it worth something, in the end? Leaving evidence of their life behind in the form of a written or recorded story seems to solidify what they experienced somehow … They are leaving behind evidence that they existed and that perhaps their life meant something.

Life story writing: enhancing your sense of self

Gillian Ednie is a life story professional who started out recording people’s memoirs or biographies after the healthcare organisation she was working for funded an evaluation of a similar biography program at Eastern Palliative Care in Victoria.

“It’s such a win-win situation,” says Gillian. “Instead of a person just being medicalised in their last days, they have the opportunity to share their life story with someone who really listens. As the process continues, the person seems to feel lighter, less medicalised and more appreciative of the life they have had. Their self-esteem increases, as does their interest in sharing their stories with family and friends, who often learn things they had never known before. It gives people a lift, a chance to reconnect, and to appreciate the lives they have shared while they still can.

“After the evaluation program, I thought, why wait till people are palliative? People should be doing this a lot earlier!” says Gillian, who then started researching life story writing as a business and went on to set up her own business, Your Biography, in 2009.

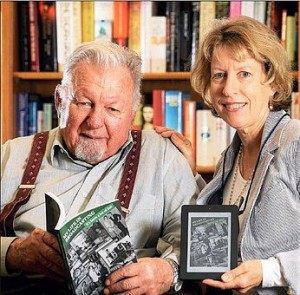

One of her recent clients is ex-broadcast journalist, 82-year-old Cliff Peel. Cliff wrote the first chapter of his own biography but could not continue after he developed macular degeneration, so he sought Gillian’s help.

“I would tell people stories from my life, and they would say ‘why don’t you write a book about it?’” says Cliff. “I just thought I was having an ordinary life, but people would tell me it was unusual … that I was doing things people don’t normally do … so that’s what prompted me to start it.

“Throughout the process, I would look back and go, ‘Hmm, I really have had fun’ – so that’s the subtitle of my book [My Life in Broadcasting: It’s Been a Lot of Fun, available on Amazon.com]. Ultimately, I learnt more about myself through the process.”

The book was launched at Cliff’s 80th birthday in 2016. “We had a bit of a party. I thought, I’m not going to be around for my wake, so I’ll have a good 80th birthday. At least I’ll be able to talk to people who come along!” says Cliff.

Gillian has worked with a number of older people on their memoirs – and some younger ones.

“I find the most interesting part of it is how people get those ‘aha’ moments about their own life,” says Gillian.

“People find a way to reframe things that have happened in their life, that they may have put away in the cupboard for many years, and not wanted to look at. So it can have therapeutic benefits too, because people are able to process the things that they couldn’t at the time.

“And they have a greater regard for themselves – to look back on their lives, and say, ‘well actually that was remarkable! I wonder how I ever did that?’ They can be very impressed with their achievements, how they handled difficult times, and the wisdom they have gained.

“I had a client who was 92, and who wasn’t a particularly reflective type of person. I encouraged her to reflect, and by the end of the process, she told me that the process ‘had given her footings’ – a sense of place in the world that she hadn’t had before,” says Gillian.

Another client of Gillian’s was a 52-year-old man who had suffered with depression and dyslexia.

“He wanted to review the past and reset the future,” says Gillian. “He’d transcended these big issues in his life, and he wanted to share his story, so that others might benefit.”

Cliff Peel and Gillian courtesy of The Leader 2016.

Alison Crossley

The health benefits of telling your story

Alison Crossley is a registered psychologist who worked in mental health for a decade, prior to moving into life story work in 2016.

Alison and her husband Paul English, who has a background in film production, record people’s life stories on video.

“Paul interviewed his mother in 2015 for her 90th,” says Alison. “He put a short film together and showed it at her birthday. She died five months later, so we were able to play some snippets from the movie at her funeral, and the priest said to Paul, ‘This is the first time I’ve had someone speak at their own funeral!’ It left us with a lovely memory of her. She made us chuckle at the funeral – she had a great sense of humour.”

After that, Alison and Paul began researching the benefits of life story work and storytelling for business, as background for setting up their own business – My Business, My Story.

“We found that there are a lot of psychological benefits in telling your story. It can help validate your life and acknowledge your achievements,” says Alison. “It can help with identity, particularly if a person is in palliative care or if they have a chronic illness where their identity is really challenged.

“It can be cathartic and healing; it can lift mood. Older people often struggle with depression and anxiety; they might have a fear of death. Telling your life story is a powerful way of helping to ease that, and helping you understand what the purpose of your life has been.”

Purpose – a robust predictor of mental health

A neuropsychologist at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center in Chicago undertook a study tracking purpose in life as a defining feature in mental health. Patricia Boyle and her colleagues tracked 1000 people over seven years, with the average age of around 80. They found that people who had a high level of purpose were more than twice as likely to remain free from Alzheimers, had 30% less cognitive decline and half the mortality rate. They also found a strong sense of purpose created more satisfaction and happiness, better physical functioning, and better sleep.1

“They found that people want to make a contribution,” says Alison. “They want to feel part of something that extends beyond themselves. The researchers particularly mentioned mentoring – passing one’s memories or experiences on to younger people – as a way to encourage a sense of purpose.

“As we age, we can lose a lot of flexibility in our mental health and the idea of telling your story or reminiscing through life storytelling can help you get a stronger idea about who you are as a person and your value in the community and the world – particularly if you are telling that to a younger generation.”

It’s also good for young people to know where they come from. In another study, a team of psychologists from Emory University in the Atlanta in US measured children’s resilience and found that those who knew the most about their family history were best able to handle stress, had a stronger sense of control over their lives and higher self-esteem. The reason – these children had a stronger sense of ‘intergenerational self’ – they understood that they belonged to something bigger than themselves.

“This kind of reminiscing can start a dialogue and help to form a bond between the teller and the listener. That’s what storytelling does. It forms a bond,” says Alison.

“Story telling engages and connects people – that’s why stories are important. There’s that quote ‘facts tell, stories sell’ – you can tell people facts till the cows come home, but if you tell them a story, it lives in the heart forever, just like that old Native American proverb says.”

“Tell me the facts and I’ll learn. Tell me the truth and I’ll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.”

References

1. Effect of a Purpose in Life on Risk of Incident Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Community-Dwelling Older Persons. Patricia A. Boyle, PhD;Aron S. Buchman, MD;Lisa L. Barnes, PhD; et al David A. Bennett, MDArch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):304-310. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208

2. Fivush, R., Bohanek, J.G., & Duke, M. “The intergenerational self: subjective perspective and family history.” In F. Sani (Ed.). Individual and Collective Self-Continuity. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2008. p. 131-143.

Heather Millar, zestcommunications.com.au, lifestoriesink.com.au

Social