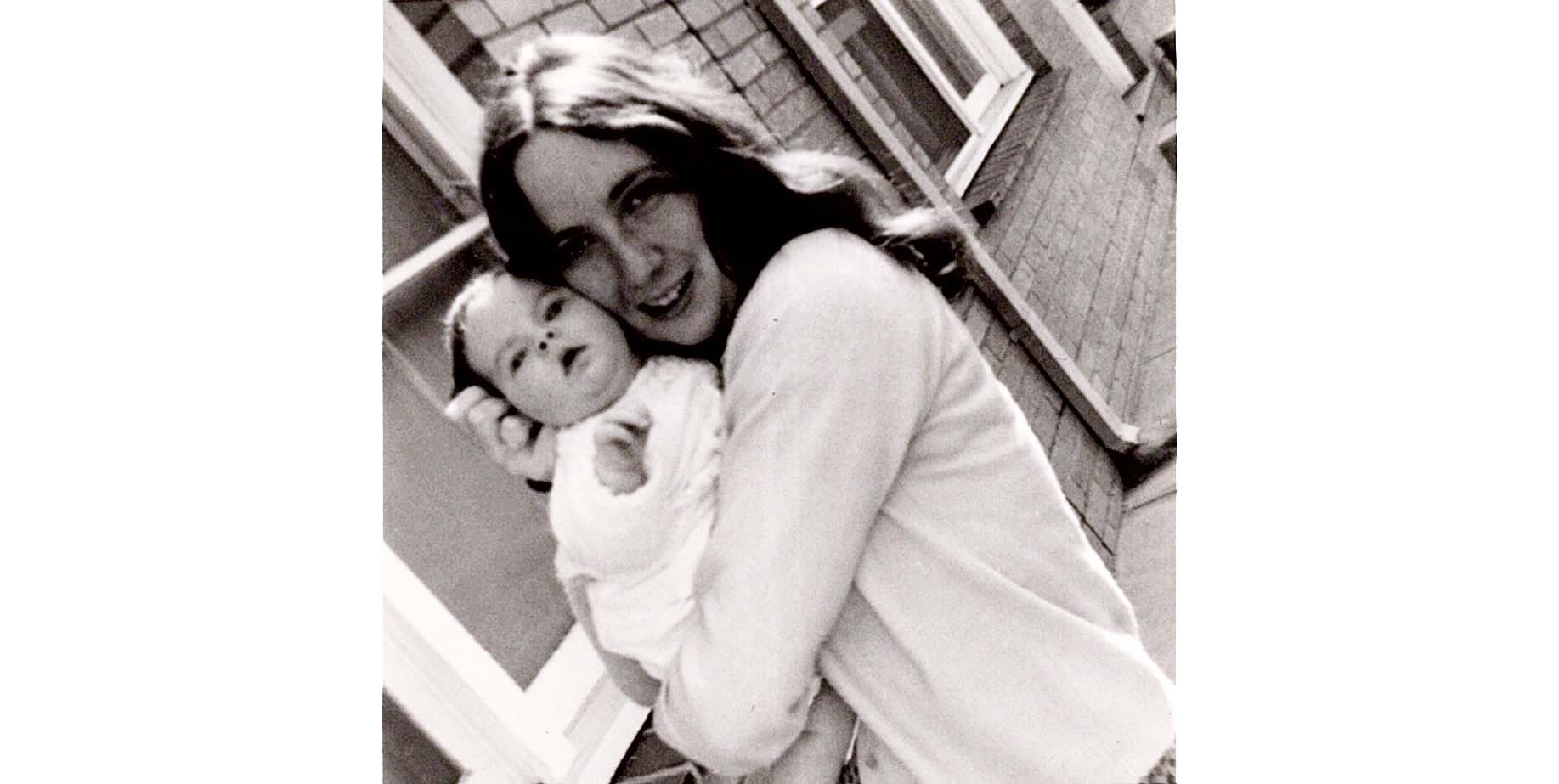

Right now we are all thinking about our mothers and ways to be in touch with them during Mothers’ Day, but I have been thinking about my mother’s story. She saw the Beatles at 14, was married at 16, had a baby (me) a year later and was a single mum by the time I was 12. Then she went back to school and became a teacher. She lived the 1960s and 1970s in nearly every way possible – teen pregnancy, music, free education and feminism – although not the drugs she tells me.

I know her story, mostly from hours of being in the car with her, but the parts I know I have not recorded in any way. It nags me that I should write my mother’s story. As a life story teller I feel like that builder who never quite gets around to that odd job in their own house.

Around Mother’s Day we are either planning how we will be in touch with our mothers, writing cards of thanks to them or wondering how we will remember them if they are no longer around or illness means they are not the woman we knew.

For many of us, our mother is hugely influential on our lives, helping form our personality, our ambition, our sense of self – our core. Yet how many of us ask just who is our mother? What was she like when she was a girl? Who influenced her? What would she have been in a different world with different opportunities? What was it like for her growing up and how does she feel about it now? Most importantly, just what is my mother’s story?

Why women’s stories are untold

And the question is why we don’t record our mother’s?

Part of it is a reflection of what is presented as history. A study of the best-selling biographies of 2015 found that 71 per cent were based on male subjects. In 2015 also, Wikipedia became so worried about the gender balance of its biographies that it introduced Women in Red to redress the problem. According to Women in Red, as of May 5, 2020 just 18.39 per cent of biographies were about women that is only 314,089 of our 1,708,248 biographies on the English Wikipedia site. After five years, the improvement was three per cent.

In 2017, women biographies accounted for just 11.6 per cent of all biographies in the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

No wonder we are not recording our mothers stories.

Organisations like Global GLOW are trying to redress the problem for girls under 30 with its HerStory campaign but where does that leave women over 30?

“Ordinary women” (if ever there was one?) have important stories to tell about the social change within society, they lived through it. Women are essentially the keepers of family folklore, they know the poignant stories that have had an impact on how our families were formed. Most importantly, their stories have meaning to our family, and if they wish to share it, to their community.

Excuses of the age

“Who would want to read my story?”

As professional life story tellers at Life Stories Australia, we know many women are reticent to begin telling their stories. Here are some of their responses to family and friends who ask them to record their story.

“I don’t like talking about myself. I’m embarrassed.”

“I was taught not to talk about myself.”

“Who would want to read my story?”

Oral history academic Dr Nikki Henningham has worked to change the gender balance on oral history in the National Library of Australia. Specifically, she has interviewed women lawyers, farmers and Jewish leaders. In her experience, women aged up to about 70 were more easily convinced to tell their story. This was partly because of the journey they took as the first generations of women to enjoy free tertiary education. Women aged over 70 often needed more convincing.

“The politeness is really hard to combat but once you get people talking they realise there is something to talk about,” Dr Henningham said.

Those stories can include thriving and surviving wars, grief, hardship, epidemics, migration, rebuilding, and technological, economic, political and social change.

Besides by not telling their story, they are missing out on an opportunity to unpack their lives. It gives them a sense of themselves. They can celebrate their achievements and those achievements do not necessarily have to be in the workforce.

Modesty and humbleness are denying families the ability to really know family folklore and to have a deeper understanding of often the most influential person in our lives.

Where to start with my mother’s story

Some of us do not know where to start. Life Stories Australia can put a person in touch with a professional storyteller who can collate a mother’s story. They draw together her recollections and present them in an easy to digest way. This is not the end of the conversation. Once family members watch, listen to or read their mother’s life story they will have many more questions. In knowing their mother or grandmother better they will have a trove of topics to talk about.

But how can professional storytellers hear those stories we never knew existed?

One of the benefits of talking to an interested stranger, albeit a paid one, is that they can ask questions in an open way. They ask questions and listen to answers for a living. There is no fear that we have heard those stories before because they are all new to us. We can ask questions that might not occur to a family member who thinks they have heard it before. They may have only heard part of it. Where an LSA member interviews them they can be assured that their embarrassing story will not be repeated. They can also speak of people they have known and loved but do not talk about anymore because it is too painful for others in the family. They can talk about themselves in their prime. It is invigorating for the person telling the story.

As I contemplate this Mother’s Day without my mother, I want to know more about my mother’s story. She still has so much to teach me. Besides, that book she wrote about my female ancestors who settled Melbourne’s western suburbs, they need their place in the Australian Dictionary of Biographies. There is so much she would have asked them if she could.

Deborah Gough

Follow Us